Finding Seneca Village in Central Park

℅ NPS

How rectified maps, ground radar, and soil samples fit pieces of a larger puzzle

The year is 1807 and a 20-year old surveyor by the name of John Randel, Jr. is faced with a rather herculean task for his youth. At the request of the New York City Commissioners, he should survey and would complete — over a period of 14 years, from 1807 to 1820 — a detailed atlas of the island of Manhattan.

With tools of his own invention and design, calculating with a precision and obsessiveness unparalleled by his peers, Randel would grind away at his assignment, tenaciously traveling northward. He ‘hiked the island’s hills, waded through its creeks and marshes, and let the tide rise up to his shoulders for more than a decade as he laid down the grid plan.’ It is a picture of purposefulness offered by biographer Marguerite Holloway in The Measure of Manhattan. Randel measured the island undaunted, placing posts and monuments on every corner of 12 Avenues and 155 blocks that would become the Grid of 1000 Intersections.

Should we travel back in time to this period and scope our environment, it would not be hard to understand what has been demanded of Randel for a system of uniformity and order. Faced with exploding population figures, animals dominating trash-strewn streets, sanitation methods failing to curb spreading diseases, legislators believed in clean slates.

But those disturbing conditions were magnified in the more densely-crowded urban areas of Lower Manhattan. Moving further north, rural landscapes and serenities of swamps, forests, hills, and rivers prevailed. Had we worked with Randel in those natural settings of today’s Central Park, where our bolts would mark street corners from West 83rd to West 89th Street, we might have come across a different and surprising world. We might have just encountered a place with around 260 residents called Seneca Village.

It is a village destined to be memorialized through Randel’s maps. A village with a name. Stretched across land where bolts would demarcate boundaries. 3 Churches. 1 School. Many houses. Many families. An integrated community — the first and most unique of its kind — of free African-American property owners and Irish immigrants. Upon Randel’s approach, with his surveying incursions into their lands seen as trespass and oncoming threat, it would not be surprising if our young surveyor and his crew were often chased away by these residents, pelted with vegetables, or met with attacking dogs.

But their fears were not unfounded. Across Manhattan, other property owners protested Randel’s imagined streets for their irreversible impact on lives and livelihoods. Notwithstanding, to make way for Central Park in 1853, the city took control of Seneca Village’s land through eminent domain. Its 260 community members — along with those 1,400 other residents of acres slated for the Park — were asked to leave. Seneca Village was demolished, all traces of its community members erased, its 30-year history Forgotten.

The Past Present

To walk through this area of Central Park in the present is to learn how science and emerging technologies are uncovering secrets of the past. Through the work of the Institute for the Exploration of Seneca Village History, we are now witnesses to an unveiling, as a team of historians and archeologists present us with gradual discoveries from their excavations of six areas within the former site. Led by archeologists Nan Rothschild and Diana diZerega Wall, the team shares some efforts undertaken since 2011 to illuminate a portrait of a Village now lost. Breakthroughs — aided by what is employed in their work of map rectification, ground penetrating radar and soil borings — peel back layers of the last 170 years, pulling us back to imagine what might have transpired in daily living. When the sounds of residents’ footsteps, voices, greetings, conversations and routines were heard.

Map Rectification

How it works:

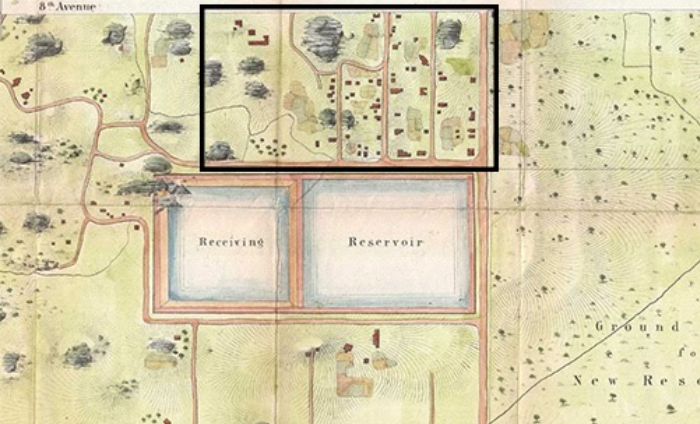

Detailed maps of Seneca Village are superimposed over maps of modern Central Park. The village is shown on John Randel’s Map of the 1811 Commissioners Plan (1821), Gardner A. Sage’s Central Park Condemnation Maps (1856) and Egbert Viele’s Sanitary and Topographical Map (1865).

What is revealed:

• Grids through land

• A neighborhood in today’s Central Park between West 83rd and 89th Streets

• Details of property layout and built structures in today’s Central Park

• Original boundaries and waterways of Manhattan

Ground penetrating radar

How it works:

An electromagnetic pulse is sent down into the ground to measure soil density, with differences indicating the presence of structures distinct from the soil in that area.

What is revealed:

Thousands of artifacts representing middle-class life, among them:

• tiles

• unmatched dishes

• houses on stone foundations

• wood sidings

• iron sheets or tiles

• William G. Wilson’s house

• child’s shoe uncovered in the Wilson house

• site of Elizabeth Harding’s house

• teapot found near the site of Elizabeth Harding’s house

• handle of a bone toothbrush

• stoneware jar lid

• glass fragments from a candlestick or lamp

Soil borings

How it works:

Several shallow cores are taken out of the sediment, mapping where layers of soil from Seneca Village remained undisturbed.

What is revealed:

• The less complex soil layers of Seneca Village unearth and confirm a rural area left almost intact.

As stories of Seneca Village are rewoven with each new discovery, we hear more hush than full melody, few notes that barely echo the full symphony clamoring for recognition. The insights of archeologist Diana diZerega Wall temper our hopes and expectations, but have us reach further for perspectives:

“However, these were official records that did not tell us much about the dreams and fears of the

people who had lived in the village, or about their daily lives. We did not have diaries or letters left

by the people of Seneca Village, and most of the descriptions that we had of the village and the

people who lived there were discriminatory.”

We welcome you to join us for a tour of Central Park or its Northern Woods for traces of a city before the Manhattan Grid. Complement our stroll with the Central Park Conservancy’s accounts of Uncovering Seneca Village, along with Seneca Village Unearthed, an online exhibit and collection of nearly 300 artifacts housed in the NYC Archeology Repository of the Landmarks Preservation Commission You may also reach for Marguerite Holloway’s The Measure of Manhattan, her story of John Randel, Jr. illustrated with dozens of historical images and antique maps.